Dream About a Baby Black Panda With a White Belly

| Ball python | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Gild: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Pythonidae |

| Genus: | Python |

| Species: | P. regius |

| Binomial name | |

| Python regius (Shaw, 1802) | |

| |

| Distribution map of ball python | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The brawl python (Python regius), likewise chosen the purple python, is a python species native to West and Fundamental Africa, where it lives in grasslands, shrublands and open forests. This nonvenomous constrictor is the smallest of the African pythons, growing to a maximum length of 182 cm (72 in).[2] The proper name "brawl python" refers to its tendency to whorl into a ball when stressed or frightened.[three]

Taxonomy [edit]

Boa regia was the scientific proper name proposed by George Shaw in 1802 for a pale variegated python from an indistinct place in Africa.[iv] The generic proper name Python was proposed by François Marie Daudin in 1803 for non-venomous flecked snakes.[5] Betwixt 1830 and 1849, several generic names were proposed for the same zoological specimen described by Shaw, including Enygrus by Johann Georg Wagler, Cenchris and Hertulia by John Edward Grayness. Grey too described four specimens that were collected in Republic of the gambia and were preserved in spirits and fluid.[vi]

Description [edit]

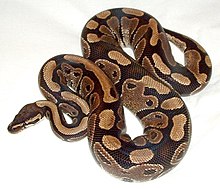

The ball python is blackness or night chocolate-brown with light brown blotches on the back and sides. Its white or cream belly is scattered with black markings. Information technology is a stocky serpent with a relatively small head and smooth scales.[3] Information technology reaches a maximum adult length of 182 cm (6 ft 0 in). Males typically measure viii to ten subcaudal scales, and females typically measure two to four subcaudal scales.[7] Females achieve an boilerplate snout-to-vent length of 116.ii cm (45+ 3⁄4 in), a 44.3 mm (1+ 3⁄4 in) long jaw, an 8.7 cm (3+ vii⁄16 in) long tail and a maximum weight of 1.635 kg (3 lb 9.vii oz). Males are smaller with an average snout-to-vent length of 111.3 cm (43+ xiii⁄sixteen in), a 43.half-dozen mm (1+ 23⁄32 in) long jaw, an 8.half dozen cm (three+ iii⁄viii in) long tail and a maximum weight of ane.561 kg (iii lb seven.1 oz).[8] Both sexes have pelvic spurs on both sides of the vent. During copulation, males utilise these spurs for gripping females.[ix] Males tend to accept larger spurs, and sexual activity is best determined by manual eversion of the male hemipenes or inserting a probe into the cloaca to check the presence of an inverted hemipenis.[10]

Distribution and habitat [edit]

The brawl python is native to west Sub Saharan Africa from Senegal, Mali, Guinea-bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory coast, Ghana, Benin, and Nigeria through Republic of cameroon, Chad, and the Central African Democracy to Sudan and Uganda.[1] Information technology prefers grasslands, savannas, and sparsely wooded areas.[three]

Beliefs and ecology [edit]

This species is known for its defence force strategy that involves coiling into a tight ball when threatened, with its head and neck tucked away in the middle. This defense behavior is typically employed in lieu of biting, which makes this species piece of cake for humans to handle and has contributed to their popularity as a pet.[3]

In the wild, brawl pythons favor mammal burrows and other secret hiding places, where they also aestivate. Males tend to display more semi-arboreal behaviors, whilst females tend towards terrestrial behaviors.[eleven]

Nutrition [edit]

The diet of the ball python in the wild consists mostly of small mammals and birds. Young ball pythons of less than 70 cm (28 in) prey foremost on small birds. Ball pythons longer than 100 cm (39 in) prey foremost on pocket-sized mammals. Males casualty more than oft on birds, and females more oft on mammals.[eleven] Rodents make up a large percentage of the diet; Gambian pouched rats, black rats, rufous-nosed rats, shaggy rats, and striped grass mice are amidst the species consumed.[12]

Reproduction [edit]

Ball python eggs incubating

Females are oviparous and lay three to 11 rather big, leathery eggs.[seven] The eggs hatch after 55 to sixty days. Young male pythons reach sexual maturity at 11–18 months, and females at 20–36 months. Age is but 1 factor in determining sexual maturity and the ability to breed; weight is the second factor. Males breed at 600 g (21 oz) or more, but in captivity are often not bred until they are 800 g (28 oz), although in captivity, some males have been known to brainstorm breeding at 300–400 g (11–xiv oz). Females brood in the wild at weights as low equally 800 chiliad (28 oz) though one,200 k (42 oz) or more in weight is most mutual; in captivity, breeders generally wait until they are no less than 1,500 thou (53 oz). Parental intendance of the eggs ends once they hatch, and the female leaves the offspring to fend for themselves.[x]

Threats [edit]

The ball python is primarily threatened by poaching for the international exotic pet trade. It is also hunted for its peel, meat and employ in traditional medicine. Other threats include habitat loss equally a effect of intensified agriculture and pesticide employ.[i] Rural hunters in Togo collect gravid females and egg clutches, which they sell to snake ranches. In 2019 alone, 58 interviewed hunters had nerveless three,000 live brawl pythons and v,000 eggs.[13]

Conservation [edit]

The Ball python is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Cerise List as it experiences a high level of exploitation so that the population has probably declined in most of Westward Africa.[1]

In captivity [edit]

Wild-caught specimens have greater difficulty adapting to a convict surround, which can result in refusal to feed, and they mostly comport internal or external parasites. Specimens take survived for up to threescore years in captivity, with the oldest recorded brawl python being kept in captivity 62 years, 59 of those at the Saint Louis Zoo.[14]

Most captive ball pythons accept common rats and mice, and some consume birds, such as chicken and quail.[15] Some keepers feed their ball pythons multimammate mice, which ball pythons would naturally feed on in the wild.[eleven] Feeder animals are typically sold frozen and thawed by owners to feed to their pythons. Another option for feeding ball pythons is with live food, where the prey is purchased alive and is either killed by the possessor and immediately offered to the serpent, or set loose and allowed to be 'hunted' by the snake. Live feeding is rarely used in some areas, such every bit the U.k., where, while not expressly prohibited, is considered a legal grayness area due to animal welfare laws which prohibit the suffering of vertebrates.[xvi] It is mostly not recommended to allow the snake to 'chase' its food as the casualty's defensive instinct can cause the prey to fight back, causing injury, and even decease to the serpent.[17] Younger ball pythons may eat as ofttimes equally every five days, but equally they mature, brawl pythons tend to await longer between meals, ranging between 7 and 14 days every bit adults. A brawl python will typically not eat when information technology is shedding.[xviii]

Convenance [edit]

Ball pythons are i of the most mutual reptiles bred in captivity. They usually are able to produce a clutch of six eggs on boilerplate, but clutch sizes besides range from one to eleven. These snakes usually lay one clutch per year and the eggs hatch around sixty days later. Usually, these eggs are artificially incubated in a captive environment at temperatures between 88–90 degrees Fahrenheit. Some convict breeders use ultra-sounding engineering to verify the progress of reproductive evolution. This can aid to increment the chances of successful fertilization as the ultra-audio tin can help predict the best times to introduce males and females during the breeding season.[19]

In captivity, ball pythons are often bred for specific patterns, or morphs.[20] While well-nigh of them are solely corrective, some have come under controversy due to inherited physical or cerebral defects associated with the inherited pattern. It has been shown that the spider morph factor is connected with major neurological bug, specifically related to the snake's sense of residual.[21] The International Herpetological Society banned the sale of such morphs at their events.[22] Convict ball pythons are available in hundreds of dissimilar color patterns.[23] Some of the most common are pastel, albino, mojave, banana, lesser, and axanthic. Breeders are continuously creating new designer morphs, and over 7,500 different morphs currently exist.[24]

In culture [edit]

The ball python is particularly revered by the Igbo people in southeastern Nigeria, who consider it symbolic of the earth, being an beast that travels then shut to the ground. Even Christian Igbos treat ball pythons with groovy care whenever they come across one in a village or on someone's holding; they either let them roam or selection them upwardly gently and render them to a forest or field abroad from houses. If i is accidentally killed, many communities on Igbo land nonetheless build a coffin for the snake's remains and give it a short funeral.[25] [ obsolete source ] In northwestern Ghana, there is a taboo towards pythons as people consider them a savior and cannot hurt or eat them. Co-ordinate to folklore a python once helped them flee from their enemies past transforming into a log to allow them to cross a river.[26]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d D'Cruze, North.; Wilms, T.; Penner, J.; Luiselli, L.; Jallow, M.; Segniagbeto, M.; Niagate, B. & Schmitz, A. (2021). "Python regius". IUCN Cherry List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T177562A15340592. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ a b McDiarmid, R. W.; Campbell, J. A.; Touré, T. (1999). Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Herpetologists' League. ISBNane-893777-00-vi.

- ^ a b c d Mehrtens, J. M. (1987). "Ball Python, Regal Python (Python regius)". Living Snakes of the Earth in Colour. New York: Sterling Publishers. p. 62–. ISBN080696460X.

- ^ Shaw, G. (1802). "Royal Boa". Full general zoology, or Systematic natural history. Volume Iii, Part II. London: Grand. Kearsley. pp. 347–348.

- ^ Daudin, F. M. (1803). "Python". Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, des reptiles. Vol. Tome 8. Paris: De l'Imprimerie de F. Dufart. p. 384.

- ^ Gray, J. Due east. (1849). "The Royal Rock Snake". Catalogue of the specimens of snakes in the drove of the British museum. London: The Trustees. pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Barker, D. G.; Barker, T. M. (2006). Ball Pythons: The History, Natural History, Care and Convenance. Pythons of the Globe. Vol. 2. Boerne, TX: VPI Library. ISBN0-9785411-0-3.

- ^ Aubret, F.; Bonnet, X.; Harris, M.; Maumelat, S. (2005). "Sex Differences in Body Size and Ectoparasite Load in the Brawl Python, Python regius". Periodical of Herpetology. 39 (2): 315–320. doi:x.1670/111-02N. JSTOR 4092910. S2CID 86230972.

- ^ Rizzo, J. M. (2014). "Captive care and husbandry of ball pythons (Python regius)". Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery. 24 (1): 48–52. doi:ten.5818/1529-9651-24.1.48. S2CID 162806864.

- ^ a b McCurley, K. (2005). The Complete Ball Python: A Comprehensive Guide to Care, Convenance and Genetic Mutations. ECO & Serpent'due south Tale Natural History Books. ISBN978-097-131-9.

- ^ a b c Luiselli, L. & Angelici, F. G. (1998). "Sexual size dimorphism and natural history traits are correlated with intersexual dietary divergence in royal pythons (Python regius) from the rainforests of southeastern Nigeria". Italian Journal of Zoology. 65 (2): 183–185. doi:x.1080/11250009809386744.

- ^ "Python regius (Brawl Python, Majestic Python)".

- ^ D'Cruze, N.; Harrington, L.A.; Assou, D.; Ronfot, D.; Macdonald, D.W.; Segniagbeto, G.H. & Auliya, M. (2020). "Searching for snakes: Ball python hunting in southern Togo, W Africa". Nature Conservation (38): 13–36. doi:10.3897/natureconservation.38.47864.

- ^ "A new squeeze? Snake mystery after lone, elderly python lays a clutch of eggs". 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ McCurley, Thousand. "Ball Python Care Sheet". ReptilesMagazine . Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "House of Commons – Environment, Food and Rural Diplomacy – Minutes of Testify". publications.parliament.britain . Retrieved 11 Baronial 2020.

- ^ Moore, Matthew (9 October 2008). "Mouse bites snake to expiry". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 Baronial 2020.

- ^ "Feeding Royal (Ball) pythons". Exoticdirect . Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Bertocchi, P. (2018). "Monitoring the reproductive activity in captive-bred female ball pythons (P. regius) by ultrasound evaluation and noninvasive assay of faecal reproductive hormone (progesterone and 17β-estradiol) metabolites trends". PLOS 1. 13 (vi): e0199377. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1399377B. doi:ten.1371/periodical.pone.0199377. PMC6021098. PMID 29949610.

- ^ Bulinski, Due south. C. (2016). "A Crash Course in Ball Python/Reptile Genetics". Reptiles magazine.

- ^ Rose, M. P. & Williams, D. L. (2014). "Neurologic dysfunction in a brawl python (Python regius) colour morph, and implications for welfare". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 23 (3): 234–239. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2014.06.002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Breeders Meetings – New Policy – June 2017". International Herpetological Guild. 2017.

- ^ Yurdakul E. (2020). "Ball Python Morphs". Reptilian world.

- ^ "Morph Listing – World of Ball Pythons". World of Ball Pythons . Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ Hambly, W. D.; Laufer, B. (1931). "Serpent worship". Fieldiana Anthropology. 21 (ane).

- ^ Diawuo, F.; Issifu, A. Yard. (2015). "Exploring the African Traditional Belief Systems in Natural Resource Conservation and Management in Ghana". Periodical of Pan African Studies. 8 (ix): 115–131.

External links [edit]

- "Python regius". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- Python regius at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- Krishnasamy, Vikram; Stevenson, L.; Koski, L.; Kellis, Chiliad.; Schroeder, B.; Sundararajan, M.; Ladd-Wilson, Southward.; Sampsel, A.; Mannell, 1000.; Classon, A.; Wagner, D.; Hise, One thousand.; Carleton, H.; Trees, E.; Schlater, L.; Lantz, Thou.; Nichols, K. (2018). "Exposure to Salmonella". MMWR. Morbidity and Bloodshed Weekly Report. 67 (19): 562–563. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6719a7. PMC6048943. PMID 29771878.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ball_python

0 Response to "Dream About a Baby Black Panda With a White Belly"

Post a Comment